Ten Historic Speeches That Almost Reached the Public

Ten speeches nearly vanished, yet stubborn voices, preserved recordings, and a single bold line helped history keep moving when silence loomed. Some orations feel inevitable in hindsight, though they almost never happened. A fever, censorship, a cabinet dispute, a missing permit, or a few seconds of panic could decide whether a turning point would speak. The famous lines were not born in ease. They were hammered out in war rooms, courtrooms, radio studios, and crowded streets. What endures is not only the wording but the choice to stand when silence would be simpler. The following entries share that edge: the speech was delayed, softened, nearly canceled, or nearly erased, and then it still reached the world, reshaping what people dared to imagine next.

LINCOLN’S GETTYSBURG ADDRESS

In November 1863, Abraham Lincoln arrived at Gettysburg exhausted and visibly unwell, planned to offer only a few remarks after the lengthy featured address. Onlookers noted his pallor, the chill in his voice, and how swiftly he sought to depart, with historians later linking this to a mild case of smallpox. The speech was perilously brief, leaving little room for ornament or wandering logic. Yet that terse frame allowed him to reinterpret the Civil War as a test of democracy, delivering a measured verdict from a body that could have faltered at the podium.

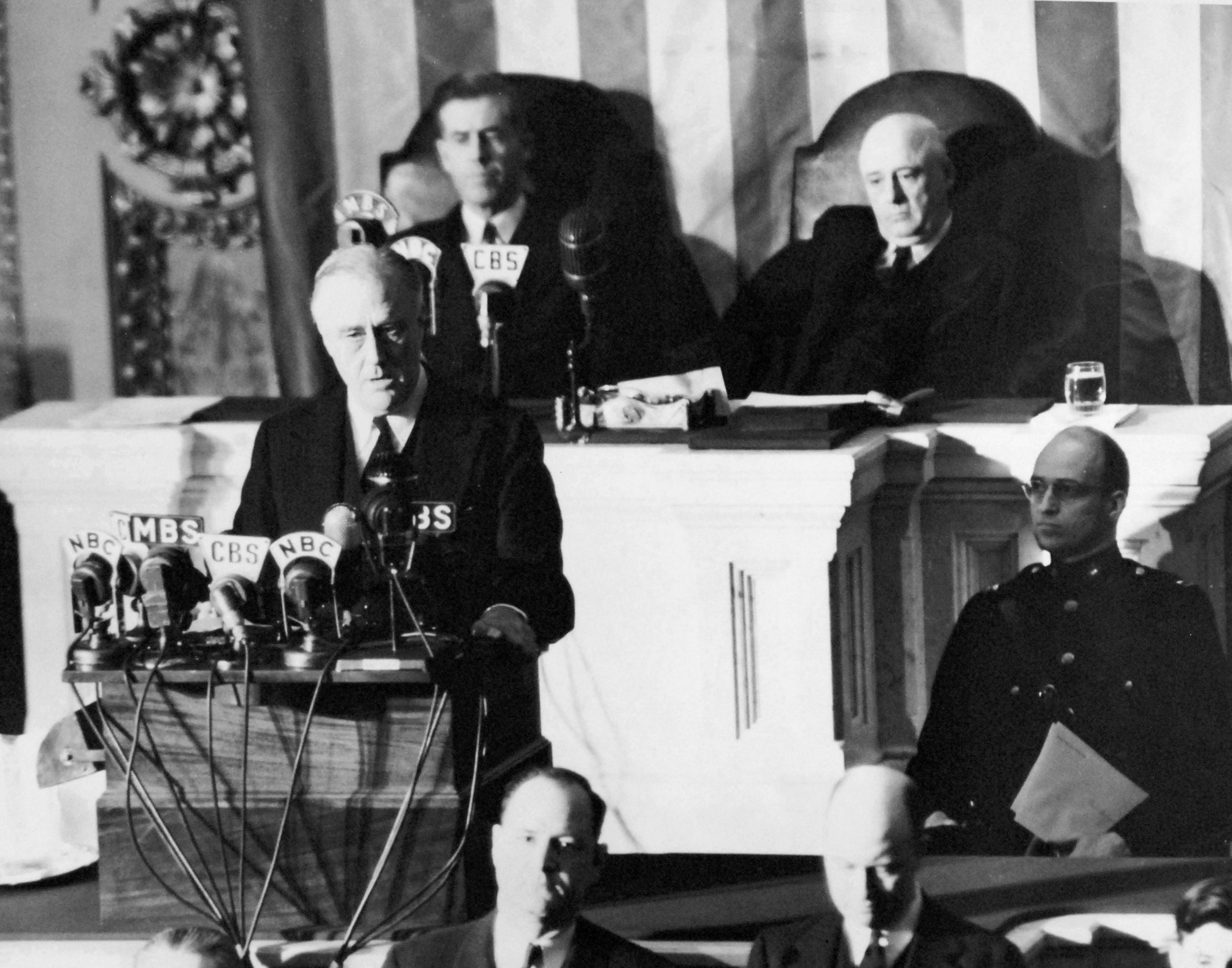

ROOSEVELT’S DAY OF INFAMY ADDRESS

Franklin D. Roosevelt presented himself to Congress on Dec. 8, 1941 as the nation reeled from Pearl Harbor, with details still shifting by the hour. Overnight, aides polished the draft, and he made a blunt but decisive opening choice, substituting a cooler phrase with the word infamy—an ethical verdict veiled as a noun. The speech might have remained a narrow briefing or a cautious appeal for patience as diplomacy collapsed in real time. Instead, he framed the attack as deliberate and unprovoked, and his steady delivery provided Americans with a common script for what would follow: unity, mobilization, and a grave, unwavering resolve, not hesitation.

CHURCHILL’S WE SHALL FIGHT ON THE BEACHES

On June 4, 1940, Winston Churchill faced Parliament with Dunkirk behind him, invasion fears mounting, and a temptation to present evacuation as victory. The rescue was real, but so was the looming threat, and his duty was to keep Britain from slipping into complacency. He coupled gratitude with warning, acknowledging what had been lost and what could still follow, then delivered the celebrated pledge of resistance across beaches, fields, streets, and hills. The list was not mere decoration; it was a mechanism to turn survival into an everyday commitment, spoken while the future still looked like smoke over the Channel.

DE GAULLE’S APPEAL OF JUNE 18

Charles de Gaulle’s June 18, 1940 broadcast was the sort of message that can vanish before it airs. Newly arrived in London and still a minor figure, he finished his text that morning and learned permission could be rescinded as British leaders worried about dealing with Marshal Pétain and the French fleet. Approval arrived late, the BBC aired him, and the message went out without the polish of certainty. No recording existed, yet the words traveled, offering a stubborn alternative to surrender and giving scattered French patriots a rallying cry as official France quieted. It mattered quickly.

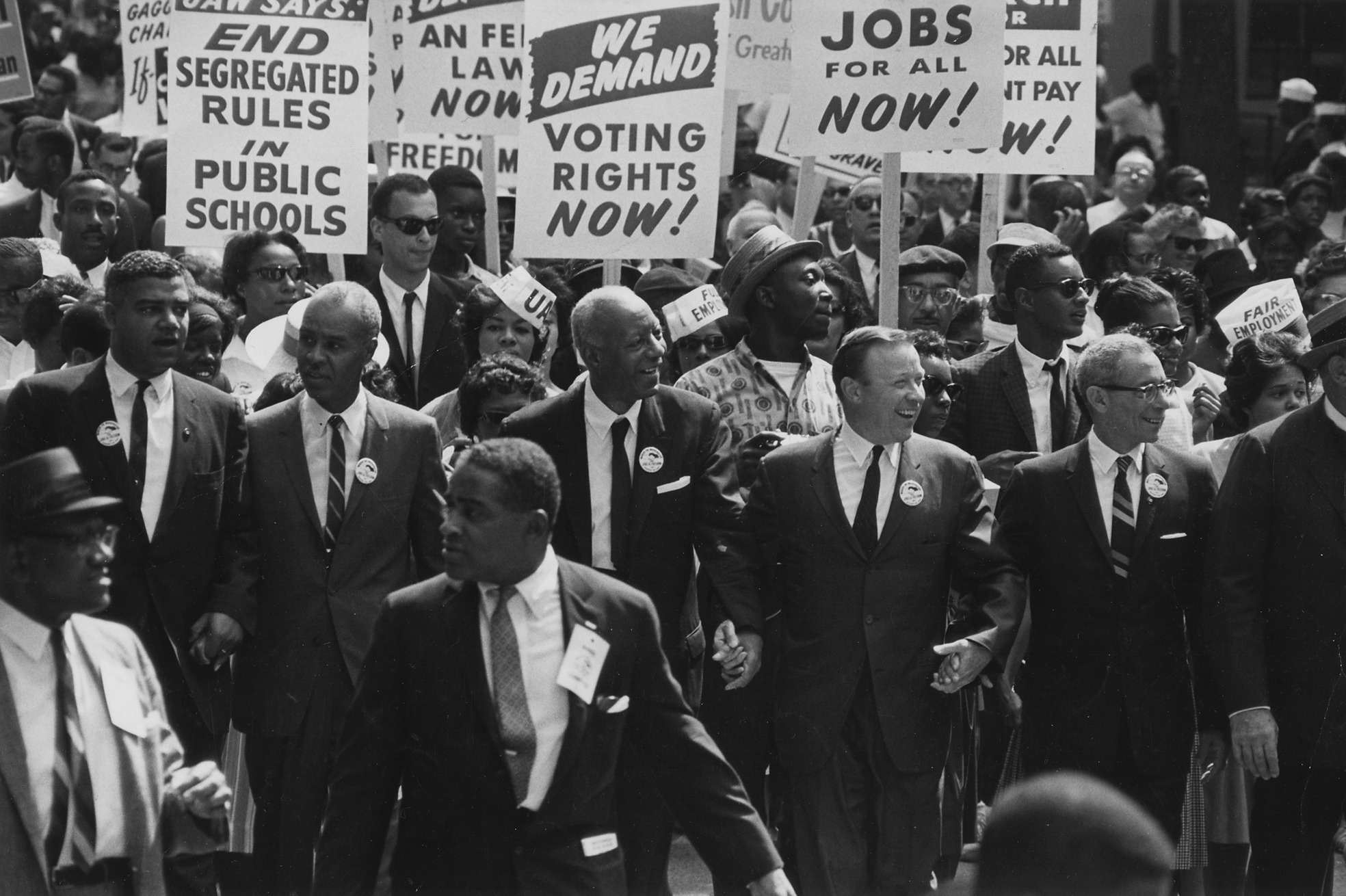

JOHN LEWIS’S MARCH ON WASHINGTON SPEECH

John Lewis arrived at the August 1963 March on Washington with a draft that refused to sound patient. At 23, he aimed to declare the pending civil rights bill too little and too late, and he directed sharp blame at both parties for asking Black Americans to wait. Senior leaders and Catholic allies warned the language could fracture the coalition on live television, prompting revisions late into the night as the program neared. Lewis spoke anyway, with the edge softened but the urgency intact, proving that even iconic moments can emerge through tense compromise. The original heat remained.

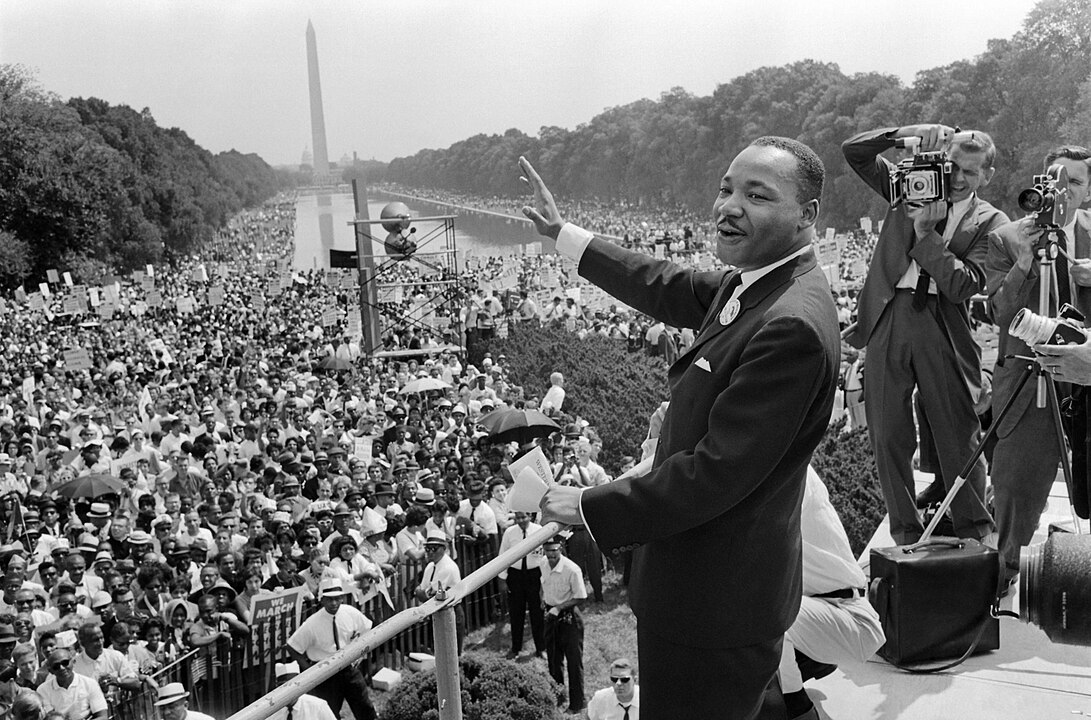

KING’S IMPROVISED DREAM

Martin Luther King Jr. did not step to the microphone on Aug. 28, 1963 intending to finish with the lines now most quoted. His prepared remarks leaned toward policy and promises and could have closed as a concise brief for change. Near the end, he shifted into the dream cadence he had used previously, driven by the crowd’s response and the sense that the moment needed uplift rather than paperwork. The moment was improvisational enough to feel like a gamble, yet it gave the speech its soaring arc, linking moral clarity to a vivid national image that endured long after the march concluded. It was never guaranteed to happen, yet it did.

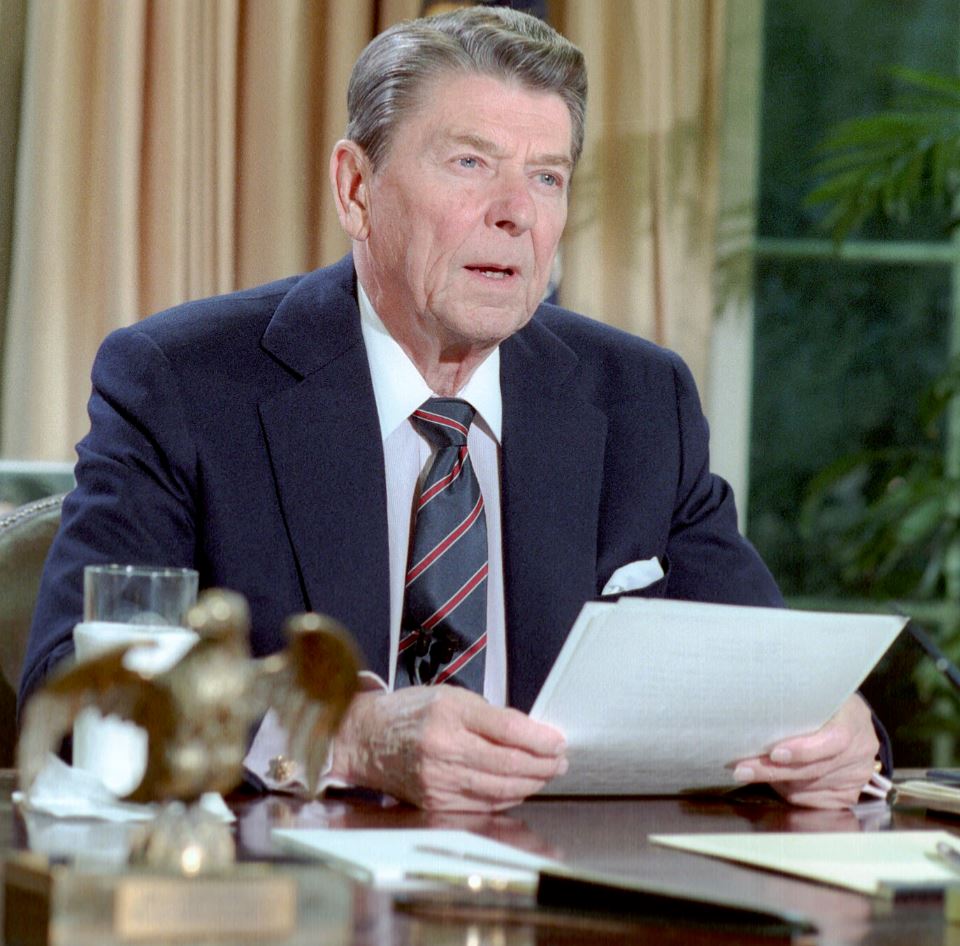

REAGAN’S TEAR DOWN THIS WALL LINE

Ronald Reagan’s Berlin address on June 12, 1987 carried a sentence that nearly died in the edits. Diplomats and State Department officials argued that directly challenging Mikhail Gorbachev and naming the Wall could inflame tensions and complicate negotiations. Drafts attempted to soften or delete the line, while speechwriter Peter Robinson insisted that clarity mattered more than etiquette. Reagan kept it, delivering it at the Brandenburg Gate, and letting the words hang as a demand the world could measure. The line survived because it faced resistance.

HIROHITO’S SURRENDER BROADCAST

Japan’s surrender announcement on Aug. 15, 1945 relied on fragile physical objects: two phonograph recordings of the emperor’s voice made inside the Imperial Palace the night before. Hardline officials attempted the Kyūjō Incident to stop the broadcast, raiding the palace to seize the discs and the guards. Courtiers hid the originals, shuffled papers to confound intruders, and secretly ferried copies to the radio station under ordinary-looking cover. At noon, the recording aired nationwide, formal in tone yet unmistakably meaningful. A few stolen minutes could have prolonged the war for days. More.

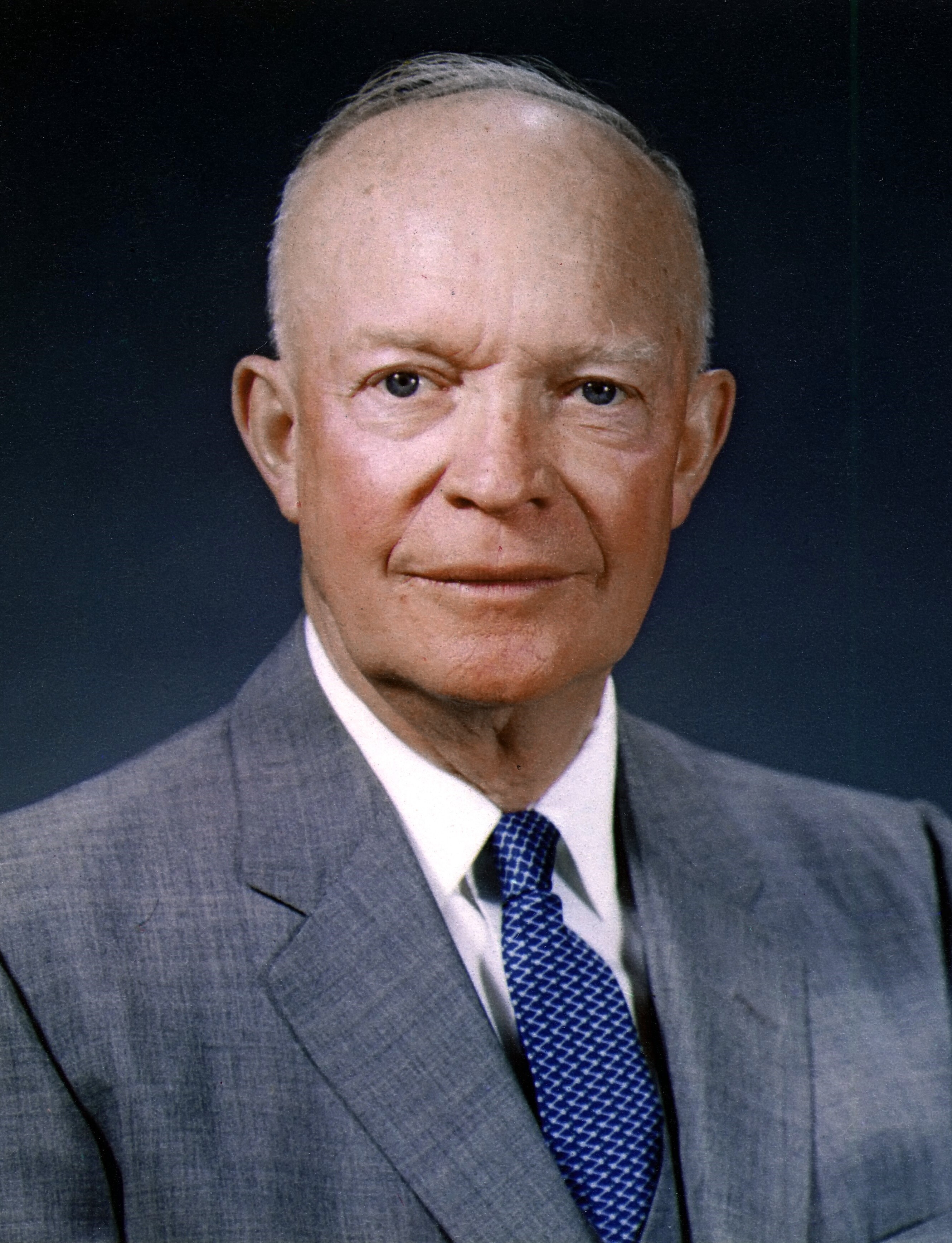

EISENHOWER’S IN CASE OF FAILURE MESSAGE

Dwight D. Eisenhower drafted one of his most revealing notes on June 5, 1944, and he intended it to stay unused. If the Normandy landings had failed, he would announce that the troops had been withdrawn and that responsibility rested with him alone. The message is short, almost stark, because it was meant for a world waking to disaster, not debate. He kept it with him as thousands crossed the Channel in darkness, bearing a commander’s private fear behind a public calm. The invasion succeeded, so the note stayed sealed, later as proof that victory is never guaranteed, even at the highest level. Tonight.

JOHN PAUL II AT VICTORY SQUARE

When John Paul II returned to Poland in June 1979, the communist state knew it could not fully control the stage it had granted him. Officials attempted to choreograph routes, crowds, and broadcast tone, wary that a Polish pope could convert faith into public bravery. In Warsaw’s Victory Square, he invoked the Holy Spirit to renew the nation’s appearance, a line that sounded religious yet carried civic weight, and the crowd responded with confidence the regime could not script. The speech moved forward, yet carried the sense of permission granted with clenched teeth, making every sentence land with force. It moved quickly and endured.