12 Misunderstood Nursery Rhymes With Dark Origins

Nursery rhymes can feel comforting with their steady rhythms and familiar cadences, suggesting childhood remains gentle. Yet many originated amid crowded streets, stern churches, and loud political moments where jokes and warnings coexisted. Over time, darker readings attached to certain lines—sometimes supported by scholarship, sometimes amplified by modern mythmaking. That blend is the point: a tiny chant can embody fear of disease, punishment, collapse, or greed, then slip past the ear on a catchy melody. They endure because they’re memorable and because they let a culture process hard truths in miniature, repeatable form. Even when origin stories are unclear, the unease reveals what people feared and could not say aloud.

Ring a Ring o’ Roses

Often presented as a simple circle game, this rhyme remains linked to plague lore: roses as rashes, posies as protection, a cough, and everyone dropping at the end. Folklorists dispute that narrative, noting that the well-known wording appeared relatively late in print and earlier versions vary widely, sometimes lacking sneezes or collapse. What endures is less a confirmed medical code and more a cultural reflex—the urge to pin catastrophe to a tune so fear feels explainable, communal, and safely contained, even when the archive can’t confirm it. It’s a rhyme that lets dread hide in plain sight.

London Bridge Is Falling Down

The chorus sounds like gleeful demolition, but the real London Bridge spent centuries cracking, burning, crowding with shops, and being rebuilt in costly cycles. That long repair history makes the rhyme feel like a city talking to itself, revisiting the same problem because the river, the traffic, and the politics never stop pushing back. Legends about Viking attacks or buried sacrifices drift around, yet evidence is thin, and the uncertainty matters: the song communicates that icons fail, budgets run dry, and daily life is shaped by slow decay and renewal. The cheeriness can resemble whistling past scaffolding.

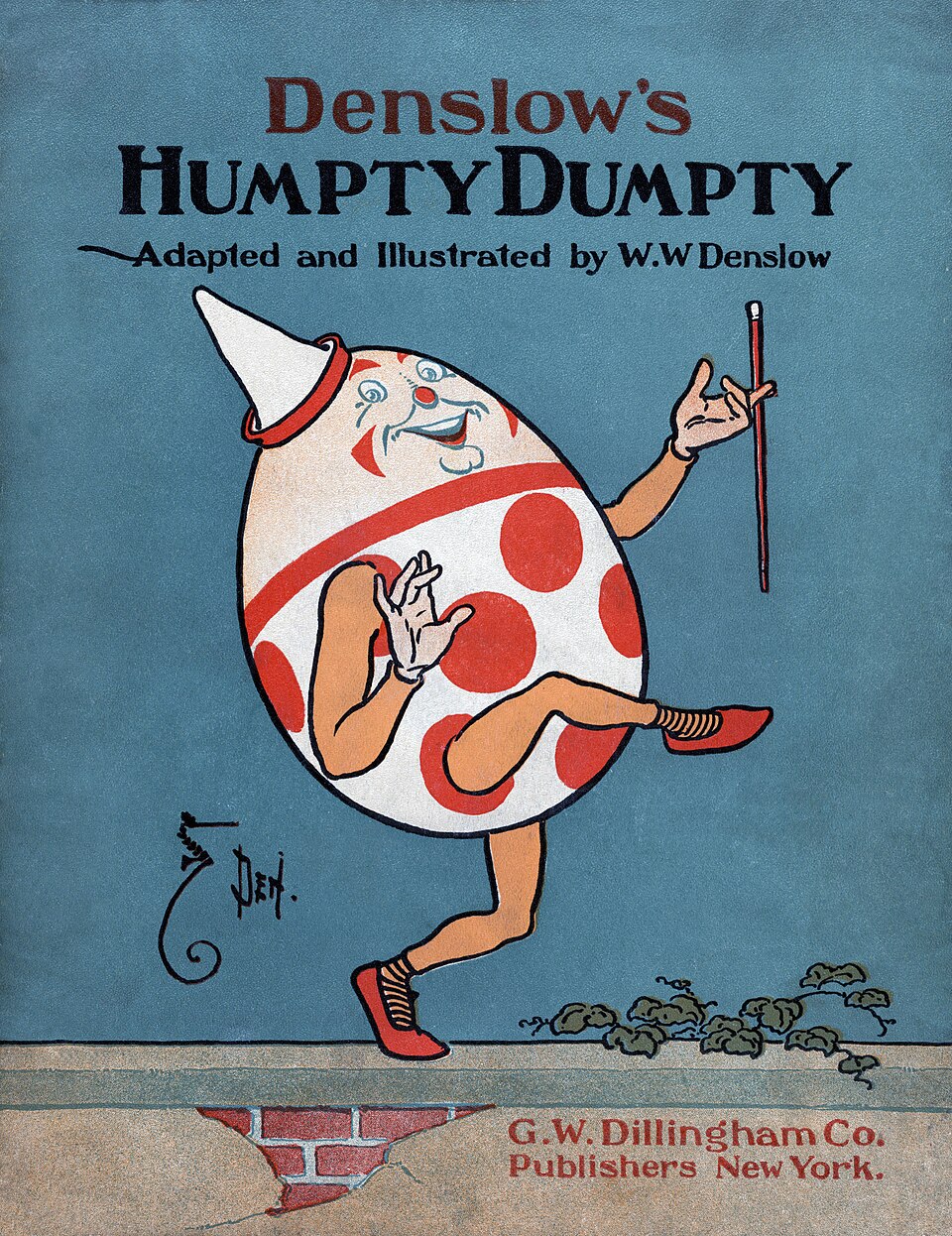

Humpty Dumpty

Before becoming a picture-book egg, Humpty Dumpty functioned as a riddle about something that breaks irreparably, regardless of any rescue attempt. The line about all the king’s horses and all the king’s men carries a blunt reminder of limits: authority can assemble a crowd, but it cannot rewind a fall, erase damage, or restore what has snapped. Tales tying Humpty to a Civil War cannon exist, though the evidence is debated, and that doubt aligns with the point. The rhyme circles back to the same ledge, where pride, balance, and chance meet and fail in public. That finality is the sting. Even the rescuers feel powerless.

Three Blind Mice

The melody glides, yet the plot follows a relentless pursuit with a cruel ending, which is why this rhyme never feels entirely innocent, even when sung with movement. A musical version appears in early 1600s print, long before children’s anthologies softened its edges, and later writers attempted to map it to persecutions under Mary I—a claim that remains unproven. Even without a verified event, the unease persists: the targets are helpless, the chase unyielding, and the refrain repeats like steps that refuse to stop, turning a nursery into a small courtroom where mercy never arrives. The tune persists. Mercy is absent.

Baa, Baa, Black Sheep

Its neat counting feels playful, but the verse centers on extraction: wool measured out and handed upward to those who did not shear it. A common theory ties the lines to historic wool taxes and the share taken, while modern claims of other exploitative systems circulate without solid early sources. What’s clear is a social mood: the best of something leaves the worker’s hands first, and obedience can be trained with a cheerful, automatic response that sounds like agreement, not resignation. The arithmetic is cute, but the arrangement isn’t.

Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary

This garden rhyme thrives on suspicion. Mary is often linked to Mary I or Mary, Queen of Scots, and the imagery reads as coded commentary, ranging from church symbols to violence. The challenge is evidence: versions shift over time, and no single interpretation sticks as fact, which is why the rhyme remains fertile ground for rumor, politics, and projection. Its darkness lies in how easily a sweet scene becomes an accusation. A few bright objects, a tidy bed, and a sing-song voice can smuggle judgment where plain speech once carried risk. The garden stays pretty, and the subtext bites. It endures because the question never truly ends.

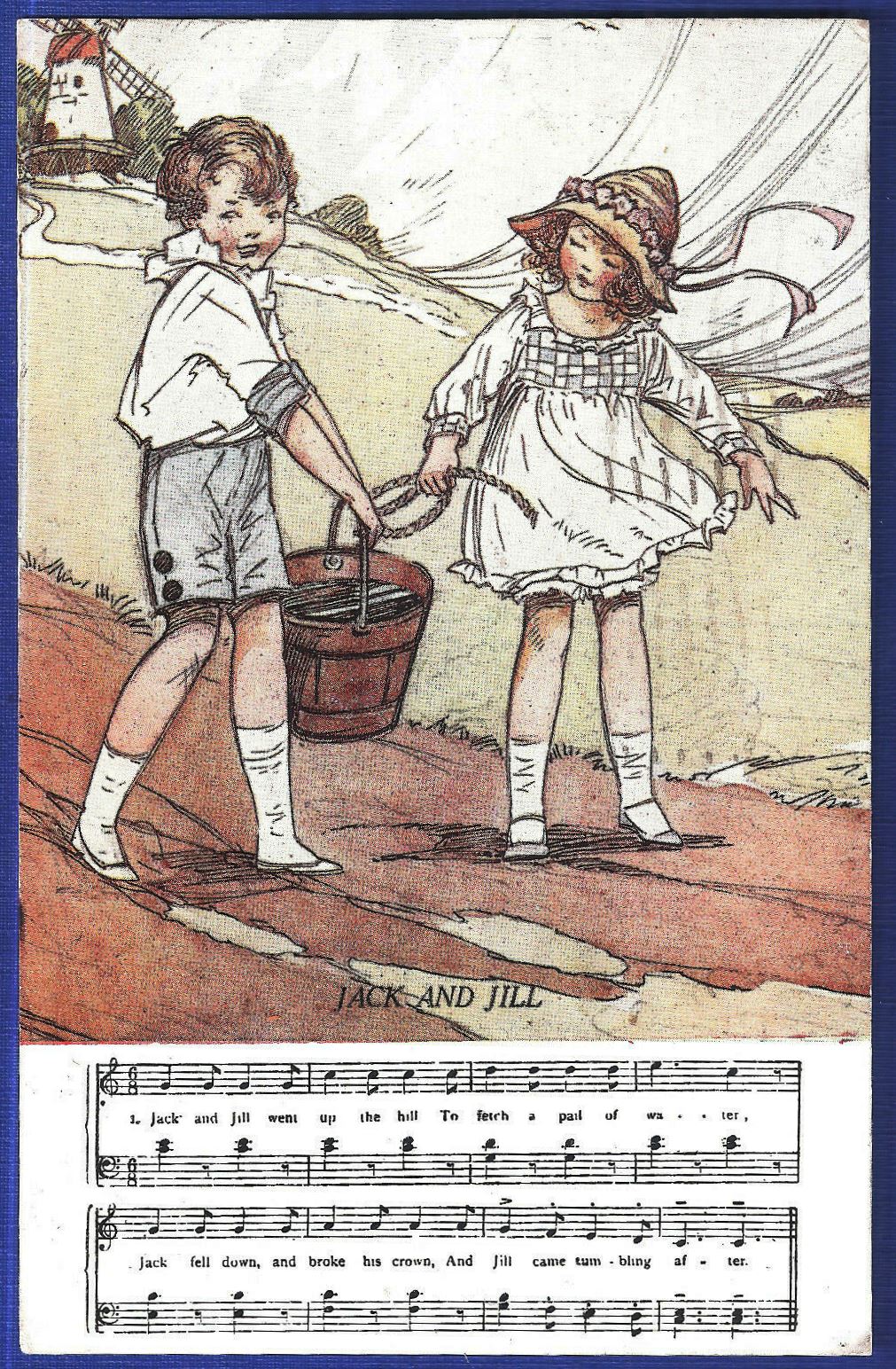

Jack and Jill

On the surface a quick trek for water, but the tumble feels symbolic, especially with a crown involved and two figures rolling together, then attempting to mend the damage. Some readings treat it as satire about rulers, missteps, or shifting measures and taxes, yet none can be proven conclusively, and the rhyme predates many tidy explanations attached to it. It endures because it candidly grapples with gravity, both literal and social. Climbing can be ordinary ambition; the fall can be abrupt, public, and hard to talk away afterward, which is why the simple scene keeps inviting reinterpretation. It reads as lighthearted on the surface, with caution underneath.

Oranges and Lemons

It begins as a bright roll call of London church bells, then tightens into themes of debt and deadlines, concluding with a later-added moment when someone is caught by the chop. Critics note that many grim readings don’t align with the earliest printed texts, yet the rhyme’s geography still points toward courts and punishments that once stood near markets and church doors. The darkness lies in the tonal shift. A city sings, time keeps ringing, and play becomes reckoning with a few added words that persist as if they were always there, like a hidden threat within a map. The bells sound cheerful until the trap snaps.

Goosey Goosey Gander

The verse moves through a house like a search, and its ending turns the domestic space into a stage for punishment, using religion as the trigger. Folklore often links the old man in the closet to eras of conflict, imagining hidden priests or forbidden worship, though the historical fit is debated and the text evolved across editions. That evolution is telling. Later versions sharpen the violence and make obedience central, as if the rhyme learned to threaten more directly. Sung lightly, it still carries the chill of coercion, where privacy offers no protection. The closet becomes a verdict rather than a hiding place.

Rock-a-bye Baby

As a lullaby, it offers calm, yet its central image is a cradle perched in a treetop, where wind and wood decide whether rest becomes a fall. The rhyme appears in 18th-century print, and some early editions even tack on a moral about pride and ambition, turning the baby’s danger into a warning about climbing too high. No fixed origin story exists, but the anxiety is evident. Comfort is temporary. Safety depends on forces that do not care about bedtime, and the song cushions that fear into rhythm so it can be endured, then hummed again tonight. It soothes by naming the fear, then riding it out. The danger stays in view.

Little Jack Horner

He seems like a harmless child with a Christmas treat, yet the rhyme has long stood for self-satisfaction and opportunistic glee, delivered with a grin. A popular tradition claims it mocked a Tudor-era Thomas Horner tied to monastery property deals, though historians debate the connection and evidence is murky. Even without that backstory, the stance sticks. Jack plucks the prize from the middle, proclaims himself virtuous, and expects applause. The darkness is moral: luck becomes virtue, and taking becomes bragging, a lesson that ages poorly for the reasons it’s cited. One small plum becomes a whole worldview.

Sing a Song of Sixpence

The opening is pure whimsy, then the rhyme shifts to money, labor, and sudden cruelty, as if a curtain falls mid-song and no one stops singing. Commentators debate whether it hides court satire or is simply a stitched-together jumble, but the counting house and the poor maid anchor it in class and vulnerability. Its bite comes from contrast: wealth indoors, work outside, and the price of being small arriving without warning, delivered on a sunny tune that keeps smiling as it repeats, so the sting lands after the last note. It’s sweet on the surface and sharp beneath.

These verses endure because they adapt to a community’s fears, jokes, and unspoken questions. When meaning stays fuzzy, the feeling still lands, and the tune keeps history alive in the present.