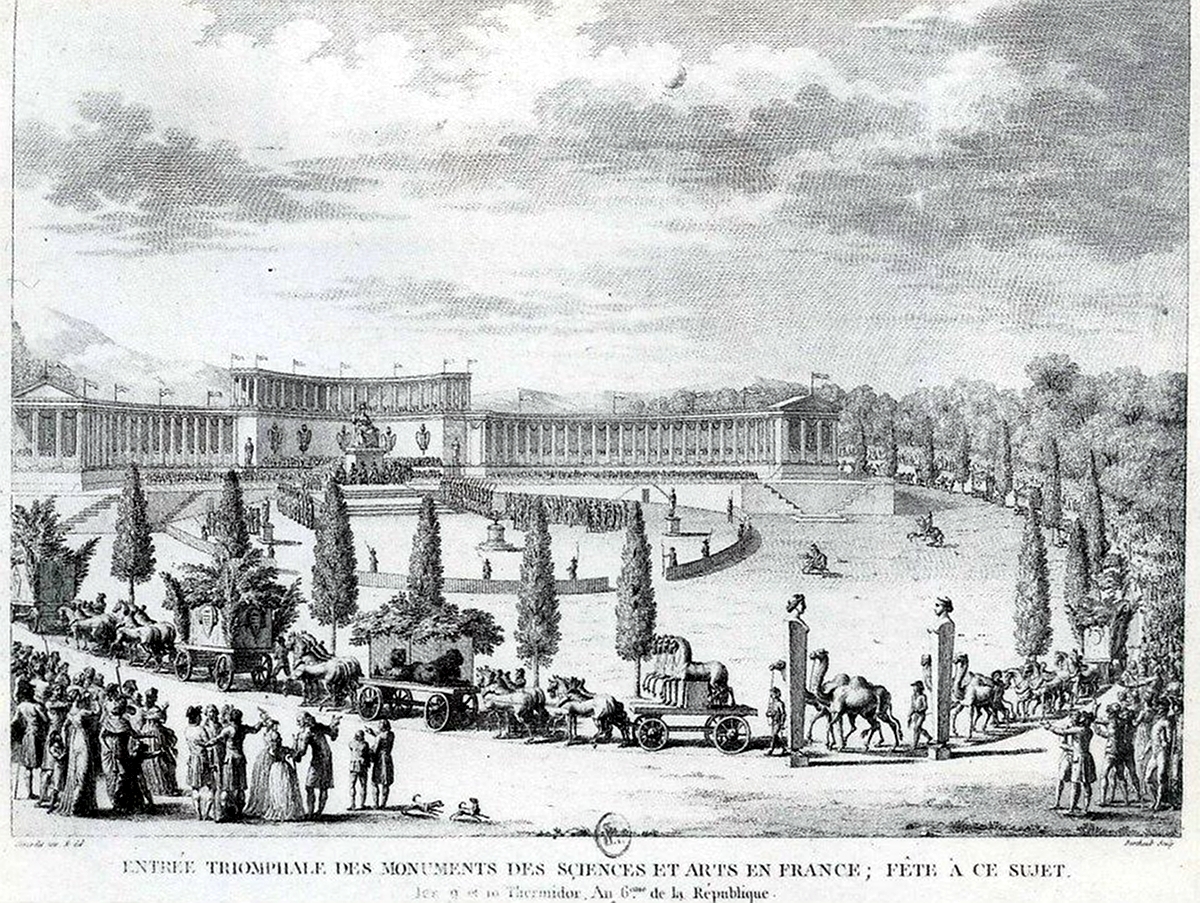

Napoleon’s Italian Loot: A Tale of Treasure Seizure

When authorities confiscate art, they rob memory along with the objects themselves. Restitution tends to be slow, but the truth tends to resurface over time.

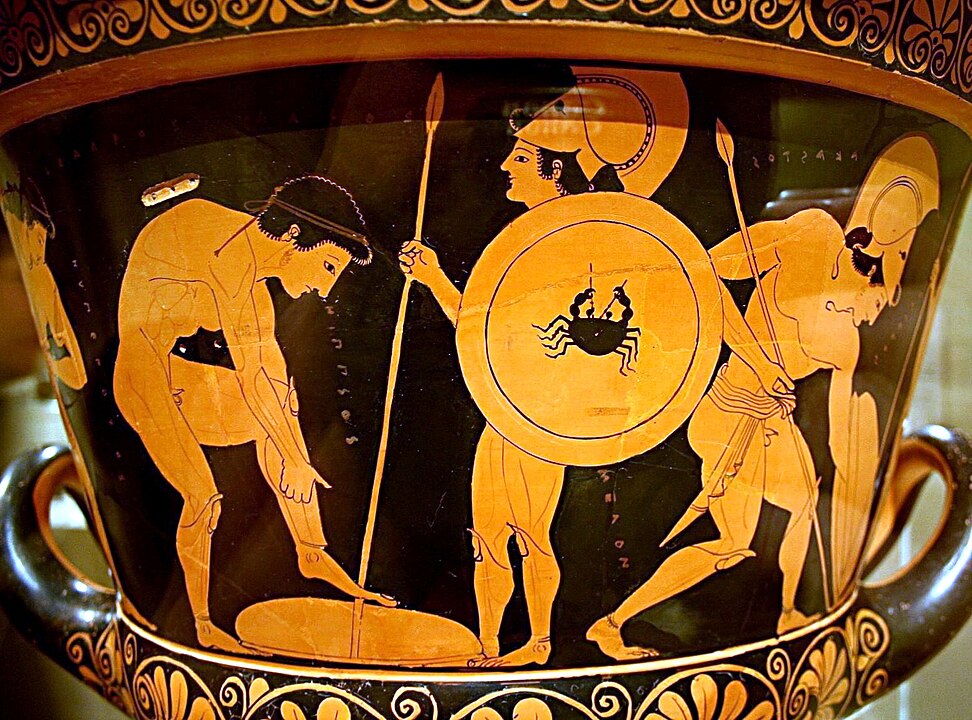

Art has long been viewed as a nation’s mirror, yet it has frequently been treated as spoils. Through revolutions, occupations, and autocratic rule, governments have seized paintings, bronzes, and sacred items not by fair purchase but through edicts, raids, and paperwork that cloaked coercion in ink. Some seizures were justified as protection, others as punishment or national pride, and many were later deemed unlawful or morally indefensible by courts, commissions, and public outcry. What endures is a trail of empty frames, fractured collections, and families still asserting ownership decades later. Each instance illustrates how culture can be turned into collateral when power proclaims ownership of the past. Restitution, when it happens, rarely restores what was lost.

Benin Bronzes Taken as War Booty

In February 1897, a British punitive expedition captured Benin City and removed thousands of bronzes, plaques, and ivories that carried dynastic memory in metal. The raid was treated as lawful spoil: the Admiralty confiscated the haul, auctioned pieces to defray the expedition’s costs, and distributed others to museums as the Oba was deposed and exiled. That origin story still shadows today’s restitution headlines, because even meticulous conservation cannot erase the fact that the first transfer occurred at gunpoint, under a flag, and by government order. Recent repatriations have reopened archives and family claims around the world.

Bolshevik Nationalization of Shchukin and Morozov

Following the 1917 Revolution, the Soviet regime acted swiftly to seize private wealth, pulling major art collections into the new order. Sergei Shchukin’s and Ivan Morozov’s modern French paintings were confiscated in 1918, incorporated into new museums, and later divided among institutions like the Hermitage and the Pushkin, while family names disappeared from wall labels. Even when the works were later masked as decadence under Stalin, the state retained the prize; the original taking was never voluntary, and heirs contend that public culture cannot begin with coerced surrender. The obligation remains unsettled.

The Nazis’ Jeu de Paume Sorting Room

Occupied Paris concealed a hub of plunder inside museum walls. At the Jeu de Paume, Nazi personnel processed more than 20,000 items seized from Jewish families, photographing, cataloging, and assigning each piece to Hitler’s planned museum or to figures like Hermann Göring, who visited often to select favorites. The process was at once bureaucratic and intimate: a signature, a seal, a rail car, and then an empty space where a collection once hung. Postwar restitution lagged behind, but surviving records reveal how a government can turn curation into a conduit for looting. The legacy still haunts current inventories.

Austria’s Enduring Hold on Adele Bloch-Bauer I

Under Nazi occupation, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer’s Klimt works were seized, and after 1945 Austria kept “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I” as a national treasure at the Belvedere, even as the family’s ownership claim was blurred into museum lore. Decades of refusals followed, until Maria Altmann pursued the case through U.S. litigation and Austrian arbitration; in 2006, a Vienna panel ordered the return, and crowds lined up to witness the painting’s departure. The episode shows how a state can inherit stolen art, normalize it with labels, and then call restitution a loss, even when the initial deprivation belonged to someone else.

Soviet “Trophy Brigades” After 1945

As Berlin fell, Soviet trophy brigades moved through depots, castles, and salt mines, packing paintings, drawings, and archives as compensation for catastrophic wartime losses. Many works vanished into Soviet repositories with incomplete public inventories, some kept secret for decades until the 1990s, while Russian policy later framed the removals as lawful reparations and effectively nationalized the holdings. Germany and private heirs have argued the opposite ever since: that suffering does not justify confiscation, and that a museum built from hidden crates carries a moral claim. Even now, claims stall.

Cultural Revolution House Raids in China

During the Cultural Revolution, campaigns against the Four Olds turned private homes into targets, and Red Guards confiscated paintings, calligraphy, antiques, and carved furniture as “bourgeois” evidence. Some objects were smashed in rallies, others were trucked to warehouses, schools, or museums, and ownership was rewritten as ideology: what had been inherited became suspect, and what was seized became public by decree. Families remember the sound of drawers being overturned and seals being stamped; even when a few pieces resurfaced later, the violence of the taking left no clean path back. Records rarely matched reality.

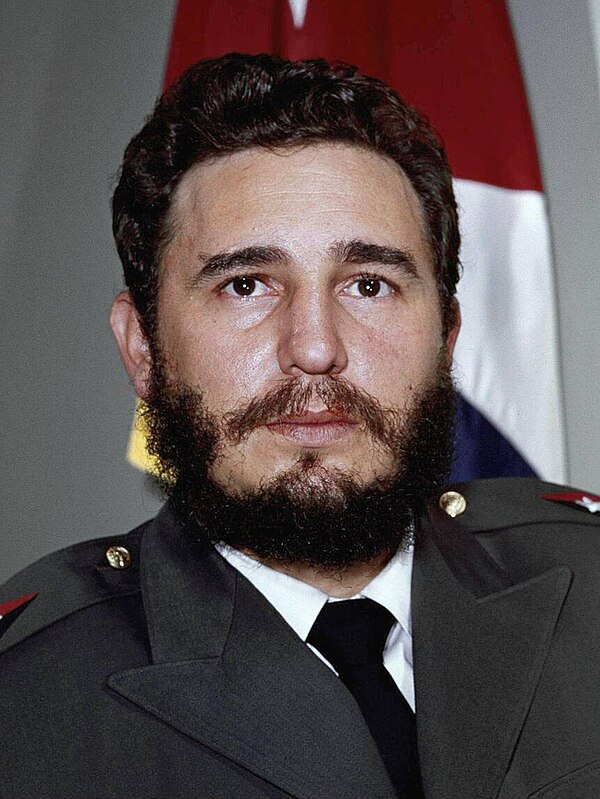

Castro’s Confiscations of Private Collections

After 1959, Cuba’s revolutionary government nationalized property on a broad scale, and art in prominent homes was folded into the same political ledger. Officials and security teams cataloged and removed paintings, antiques, and jewelry from exile households, arguing the items were abandoned or forfeited, and many pieces were absorbed into public museums without market purchase. Years later, restitution efforts encounter stalled diplomacy and competing legal theories, but the human story is clear: collections were broken in an instant, and the loss was framed as a patriotic correction. The wounds remained personal.

Franco-era Retention of Civil War “Safekeeping”

During Spain’s Civil War, authorities relocated artworks for protective reasons, but after 1939 Franco’s regime retained many of those “deposits” and folded them into state museums, archives, and ministries. Paintings, jewelry, religious objects, and furniture wore new catalog numbers while owners died in exile or under suspicion, unable to reclaim items taken in the name of safety and then treated as state heritage. Recent public lists and restitutions reveal the trick: temporary custody quietly turning into confiscation, sustained not by courtroom verdicts but by decades of silence and paperwork. Families continue to search.

Stasi-era Art Seizures in East Germany

In the GDR, art functioned as both currency and control, and confiscations grew into a quiet industry. Works were taken from citizens deemed politically unreliable, from households accused of customs or tax offenses, and from families punished for attempting to flee, then routed into museum inventories or sold abroad through state-linked dealers. The seizures were explained as law enforcement, yet later investigations suggest a significant portion of GDR-era acquisitions came from coerced transfers, leaving victims entangled in the same archives that would prove the loss. Anger endures.

Iraq’s 1990 Seizure of Kuwait’s Museum Treasures

When Iraqi forces occupied Kuwait in 1990, cultural institutions were treated as strategic targets, not protected spaces, and museum holdings were packed away as state property. Items from the Kuwait National Museum and storerooms disappeared across the border, triggering UN-backed and UNESCO-supported searches, border checks, and diplomatic pressure aimed at reversing the removal. Some objects did return, but the damage went beyond missing crates: records were fractured, collections lost context, and the idea of cultural immunity in war proved fragile for years.

The Goudstikker Gallery and Göring’s Take

In 1940, Dutch Jewish dealer Jacques Goudstikker fled as the Nazis advanced, leaving behind a cache of Old Master paintings. Nazi authorities engineered a coerced transfer of the gallery’s assets, and works were funneled into the collection of Hermann Göring and other buyers, with contracts and receipts designed to mimic consent. Postwar recovery became another ordeal: some paintings were treated as state property, others drifted into museums abroad, and heirs had to litigate and negotiate piece by piece, because a government-backed theft can be laundered into a “sale” that lasts on paper for decades still.