Earth ovens, hot stones, tea smoke, and salt shells reveal how cooks translate the natural world into technique and turn technique into daily comfort.

Memories of meals come not only from taste but from the way they’re prepared. From coastlines to plateaus, cooks view heat as something that can be tucked, trapped, stretched, or borrowed from the land itself. Stones become burners, soil becomes a lid, leaves serve as padding, and smoke is guided like a spice. Many of these methods began as practical solutions to scarce fuel, long journeys, or fickle weather, then grew into rituals for holidays, weddings, and Sunday mornings. What makes them unusual is also what makes them dependable: the cook trusts time, temperature, and restraint. The reward is flavor with a clear sense of place, nearly every time.

HĀNGĪ PIT OVEN

Hangi

In Aotearoa New Zealand, Māori cooks heat stones until they glow, lay baskets of meat and vegetables over the rock bed, and seal the pit with damp fabric, leaves, and soil so the heat cannot escape. Steam works for hours, making kūmara creamy, greens sweeter, and meat tender while keeping flavors clean rather than charred. The cook listens for time, not sizzle, because opening early disrupts the balance. When the cover is finally lifted, aromatic vapor rolls out and the food carries a gentle smokiness that tastes of earth, leaf, and careful timing. It’s well suited for crowds, keeping service relaxed.

IMU UNDERGROUND ROAST

Earth oven

In Hawaiʻi, an imu is a stone-lined pit heated for hours, then layered with ti leaves and wrapped meat, often a whole pig for kālua. After sealing with more leaves, burlap, and soil, the oven holds steady heat through the night, cooking gently without scorching fat or drying the surface. The setup is tangible and precise: bundles are lowered, the cover is packed tight, and the pit is left undisturbed so steam can work. By morning, the meat pulls into silky strands with subtle smoke and a leaf-sweet note, ready for a table built by many hands. The leaf layers also perfume the steam as it circulates.

PACHAMANCA STONE-BAKED FEAST

Bake

In Peru’s Andes, pachamanca builds an earthen oven by heating stones, placing marinated meats, potatoes, corn, and beans, then sealing the mound under soil. Because the stones cool slowly, everything roasts and steams at once, absorbing herb perfume and a faint mineral edge tied to the high altitude. Layering matters: dense tubers sit closest to heat, delicate items rest higher, and the seal keeps moisture moving through the stack like a slow tide. When the cover is removed, steam escapes and the meal arrives together, with crisp edges, tender centers, and a sense of celebration earned through patience.

GEOTHERMAL HOT-SPRING BREAD

Bread

In parts of Iceland, rye dough is sealed in a pot and buried near geothermal ground, where it bakes for about 24 hours beside bubbling springs. The slow warmth caramelizes the grain, producing a dark, moist loaf with gentle sweetness, a tight crumb, and no crust to fight. It suits a landscape where heat rises naturally and firewood can be scarce, especially in winter. The pot is set into warm soil, marked, and left alone while mineral-scented steam drifts nearby. Uncovered later, it feels like the earth kept a promise, delivering comfort with butter, smoked fish, or both.

BOODOG HOT-STONE ROASTING

Boodog

On Mongolia’s steppe, boodog cooks goat or marmot from the inside by loading the cavity with river stones heated until red-hot, then closing it so the stones radiate heat outward. The skin may be briefly seared, but the stones render fat and baste the meat as it cooks, building richness without a pot or pan. Born from travel and limited cookware, the method is both practical and ceremonial, timed by feel rather than clocks. When it’s done, the meat tastes deeply savory yet clean, and the warm stones are sometimes passed around after a long, cold ride. It’s judged by scent and texture, not gadgets.

TEA-SMOKING OVER RICE AND LEAVES

Tea

Tea-smoking turns a wok into a compact smokehouse by heating tea leaves with rice and sugar until they smolder, then trapping duck, tofu, or fish above the fragrant haze under a tight lid. The food browns quickly and carries a scent that’s floral, toasty, and lightly caramel, with bitterness kept in check by careful heat and timing. Many cooks finish with a quick fry or roast so the skin crisps while the interior stays juicy. It rewards attentive cooking, proving that deep flavor can come from pantry staples and disciplined control. A short rest helps the smoke settle. Done right, the tea note remains clean, never acrid.

DUM PUKHT SEALED-POT SLOW COOKING

Dum pukht

Dum pukht seals a heavy pot with a dough rope to trap steam, then cooks meat, rice, or lentils slowly until flavors knit together. In Awadhi kitchens, coals may sit beneath and on the lid, maintaining even heat and preventing hot spots that toughen food or scorch spices. With no vents, saffron, cardamom, and fried onions stay locked in, sinking into every grain and bite. Breaking the dough seal releases a concentrated aroma that feels ceremonial, like a curtain rising. Because the heat remains gentle, textures keep their shape and the dish tastes layered rather than muddled.

BARBACOA IN AN AGAVE-LINED PIT

Barbacoa

Barbacoa de hoyo employs an earthen pit lined with embers and maguey leaves, where lamb or goat is wrapped, lowered, and buried to cook overnight. The leaves perfume the meat and shield it from fierce flames, while drippings collect below into a broth often served as consommé for dipping. At dawn, the cover lifts to reveal savory steam and meat that pulls apart with a gentle tug. The approach makes a long cook feel like a weekend ritual, with warm tortillas, bright salsa, and a broth carrying smoke, fat, and leaf fragrance.

BAMBOO-TUBE ROASTING FOR STICKY RICE

Bamboo cooking

In regions of Thailand and Laos, sticky rice mixed with coconut milk and sugar is packed into fresh bamboo tubes, sealed with leaf plugs, and roasted over coals. The tube traps steam, ensuring even cooking while the bamboo contributes a grassy sweetness, and the exterior chars to form a protective crust. Vendors rotate the tubes by hand, listening for subtle shifts as moisture drops and the surface tightens. When opened, the rice shines with fragrance, sometimes studded with beans or taro, and is meant to be shared after markets or celebrations. The charred bamboo skin peels away like packaging, keeping the rice warm.

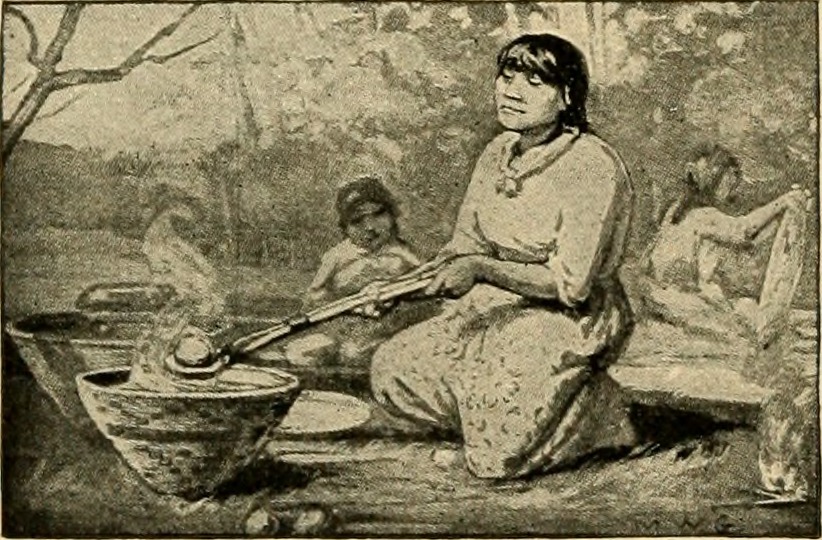

STONE BOILING WITHOUT A POT

Stone boiling

Stone boiling begins by heating dense rocks in a fire, then dropping them into water kept in a basket, hide bag, or clay-lined pit. The stones hiss, cloud the water, and bring it to a boil, cooking fish, roots, or grains without metal cookware, while fresh hot stones replace cooling ones to stabilize temperature. The choice of stones matters since some crack or shed grit, so experience guides what to heat and what to leave. The method is straightforward on paper, but it requires timing and calm hands, turning improvisation into a repeatable system. Practice makes it safe and repeatable, even outdoors.

SALT-CRUST BAKING AS ARMOR

Salt crust

Salt-crust cooking envelops fish, poultry, or vegetables in a thick damp salt layer, often bound with egg whites, then bakes until the shell hardens like stone. Inside, the food steams in its own moisture, staying juicy and evenly seasoned, while the crust blocks harsh heat and prevents surface drying. The moment of crackle at service releases clean aromas and tender flesh with minimal cleanup. It embodies restrained practicality: a single ingredient functions as seasoning, cookware, and protection, leaving the interior perfectly cooked. The crust allows for forgiving timing, which is why it endures.

SAND-BAKING UNDER EMBERS

Sand baking

In desert cooking, dough is tucked into a shallow hollow, covered with hot sand and embers, and left to bake in dry, radiant heat with the wind kept off the surface. The bread emerges, brushed clean, and opens to a tender center with a smoky edge and crisp spots where the embers kissed the crust. Built for travel and scarce fuel, the method requires little beyond flour, fire, and steady timing, and can be repeated anywhere with solid ground. It turns open terrain into a reliable oven, and the first warm pieces disappear quickly beside sweet tea at dawn. It pairs well with dates or salted cheese.