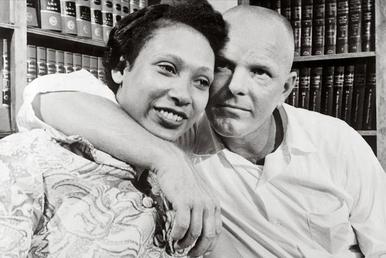

RICHARD AND MILDRED LOVING

They exchanged vows in Washington, D.C., in June 1958, then returned to rural Virginia, where their union was treated as evidence of a crime. Police stormed their home before dawn, dismissed the certificate on their wall, and jailed them. A judge suspended a one-year sentence only if they left Virginia and stayed apart for 25 years. Exile brought loneliness and financial strain, but it also clarified the issue: the state was attempting to decide their family’s fate for them. In June 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court ended Virginia’s ban, turning race-based marriage laws into a thing of the past. The victory arrived late, yet it stood firm.

ANDREA PEREZ AND SYLVESTER DAVIS

In Los Angeles in 1948, Andrea Perez, who was white, and Sylvester Davis, who was Black, were denied a marriage license because California still enforced an interracial ban. They did not seek special treatment. They challenged the rule itself, arguing that the state could not treat marriage as a privilege reserved for one race. In a narrow 4–3 decision, the California Supreme Court struck down the ban, years before Loving. The case demonstrated that a routine denial at a counter could become a constitutional argument with statewide consequences. It was a modest couple, but the ruling was loud in law.

HAN SAY NAIM AND RUBY ELAINE NAIM

Ruby Elaine Naim, a White Virginian, wed Han Say Naim, a Chinese man, in North Carolina in June 1952 because that state did not clearly forbid their match. Virginia responded by declaring the marriage void under its racial purity law, treating the vows as if they had never occurred. When the relationship later unraveled, courts doubled down and used the statute to erase the union entirely. The cruelty was procedural: a license could be valid in one place, then nullified at home, turning marriage into a trapdoor carved from jurisdiction lines. The ruling warned couples that acceptance could be revoked at first sight.

DEL MARTIN AND PHYLLIS LYON

Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon built a life together for more than five decades long before any official form could name it marriage. On Feb. 12, 2004, they became the first same-sex couple to marry at San Francisco City Hall when licenses briefly existed. The joy was immediate, and so was the backlash. The state later voided those marriages, wiping out the paperwork in an instant. They kept referring to each other as spouses anyway, and their story showed how recognition can arrive in the morning and vanish by the afternoon ruling. Their two weddings framed an era of uncertainty and steadfast determination. The politics felt personal.

EDITH WINDSOR AND THEA SPYER

Edith Windsor and Thea Spyer married in Toronto in 2007 after decades together, because the United States still refused to recognize their relationship at the federal level. When Spyer died in 2009, Windsor was denied the spousal estate tax exemption under the Defense of Marriage Act and was billed $363,053. The amount transformed grief into an argument for equal treatment under the law. Her case reached the Supreme Court, and in 2013 the justices struck down DOMA’s federal definition of marriage, compelling the government to respect lawful same-sex marriages. It did not erase their loss, but it removed a legal insult from countless families.

JAMES OBERGEFELL AND JOHN ARTHUR

When John Arthur’s health declined, he and James Obergefell wed in Maryland in 2013 because Ohio would not recognize their relationship. The ceremony was shaped by time limits, medical needs, and family, not politics. After Arthur died, Ohio refused to list Obergefell as a surviving spouse on the death certificate, affecting dignity and legal standing. Obergefell challenged the state’s refusal, and the case became the cornerstone of the 2015 Supreme Court decision requiring every state to recognize same-sex marriages. What began as paperwork evolved into a nationwide rule affirming equal citizenship in marriage.

JACK BAKER AND MICHAEL MCCONNELL

In Minnesota in 1970, Jack Baker and Michael McConnell sought a marriage license and were turned away, then lost at the state Supreme Court, which defined marriage as limited to opposite-sex couples. They persisted. In 1971, they obtained a license in another county and held a ceremony anyway, choosing to live as spouses without state approval. The U.S. Supreme Court dismissed their appeal, and for decades their partnership existed in legal ambiguity. Years later, a judge affirmed the marriage’s validity, a rare moment when the record finally matched the life already lived. Their persistence foreshadowed what courts would later accept.