History has a way of passing down stories that feel neat, tidy and convincing, even when the facts don’t hold up. Our grandparents learned many of these “truths” in school, repeated them with confidence and heard them echoed in books, films and everyday conversation. Only later did researchers, archaeologists and historians unravel the real stories behind them. What makes these moments so interesting is not just that the facts were wrong, but how easily each myth blended into the culture of its time. Looking at them now gives us a clearer sense of how knowledge evolves, how narratives stick and how curiosity keeps pushing us closer to the truth.

1. Vikings And The Myth Of Horned Helmets

The idea of Vikings charging into battle with curved horns on their helmets is one of the most stubborn images in popular history, but it is almost entirely a product of art, theater and costume design. Archaeologists have uncovered Viking helmets made of iron and leather, and none of them have horns. In close combat, protruding horns would have been a liability, catching weapons and making it easier to unbalance the wearer. The horned look really gained traction in the 19th century, when Romantic era artists and costume designers for operas like Wagner’s works wanted a dramatic, visually striking way to distinguish Norse warriors on stage. That stylized image filtered into posters, comic books, cartoons and school books, until it felt historical.

2. The Flat Earth That Medieval Scholars Never Believed In

Many people grew up with the neat story that medieval Europeans thought the Earth was flat until brave explorers proved them wrong. Historically, that just does not hold up. Since antiquity, scholars in the Greek and Roman world had argued for a spherical Earth, using observations like the curved shadow on the Moon during an eclipse and the way ships disappear hull first over the horizon. Medieval thinkers in Europe inherited these texts and taught a round Earth in universities and church schools. Figures such as Thomas Aquinas and other theologians referenced a globe without controversy. The flat Earth narrative was largely constructed in the 19th century as a way to paint the Middle Ages as ignorant and to contrast them with supposedly enlightened modern science.

3. “Let Them Eat Cake” And The Power Of A Line She Never Said

Marie Antoinette’s supposed remark, “Let them eat cake,” has become shorthand for elite indifference, but historians have never found solid evidence that she uttered those words. Versions of the phrase appear in texts written before she arrived in France, sometimes attributed vaguely to a different unnamed princess. During the French Revolution, pamphleteers and later storytellers used the line to personalize anger toward the monarchy, turning a complex economic and political crisis into a simple anecdote about one woman’s cruelty. The queen did live a highly privileged life at Versailles and was a convenient symbol for inequality, which helped the quote stick even without documentation.

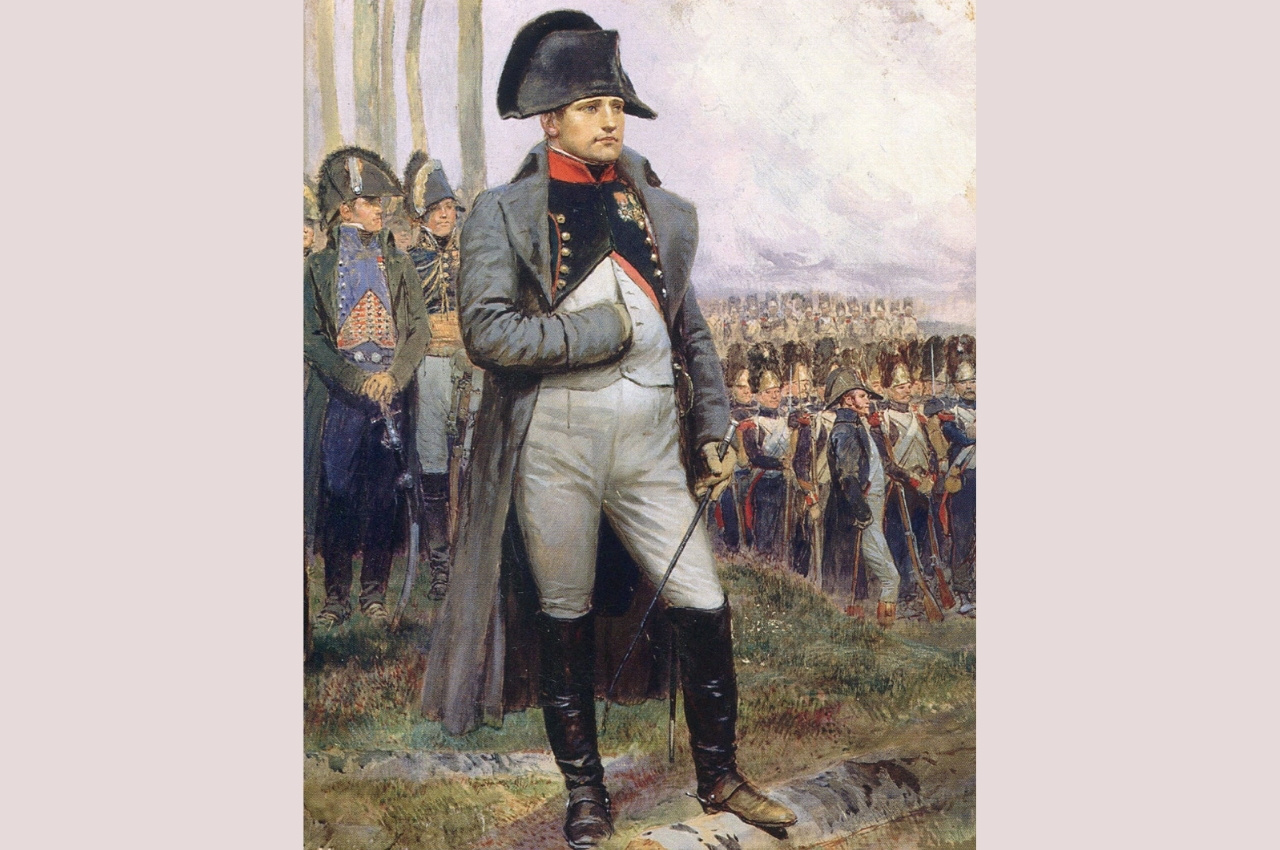

4. Napoleon And The Myth Of The Tiny General

Napoleon’s height has taken on a life of its own, with the phrase “Napoleon complex” suggesting that short men overcompensate with aggression or ambition. In reality, records from his lifetime put him at roughly 5 foot 6 or 5 foot 7 in modern measurements, which was close to average for French men of the early 19th century. Confusion stems from several sources. French inches were not identical to British ones, and British cartoonists loved to depict their rival as small and ridiculous, shrinking him on paper to make him less threatening. Those caricatures were widely circulated and left a lasting impression. Over time, the exaggeration hardened into a supposed fact that ended up in school lessons and popular culture.

5. The Great Wall Of China Seen From Space

The claim that the Great Wall of China is the only man-made structure visible from space sounds impressive, which is probably why it has been repeated so often in textbooks and trivia. Scientifically, it does not stand up. The wall is very long, stretching thousands of kilometers, but it is relatively narrow and constructed from materials that blend in with the surrounding landscape. Astronauts in low Earth orbit report that they can see cities, roads and airports by looking for contrasts in color and light, but identifying the Great Wall with the naked eye is extremely difficult, if not impossible, without ideal conditions and prior knowledge of exactly where to look. High resolution cameras and zoom lenses can pick it up, but that is different from casual visibility.

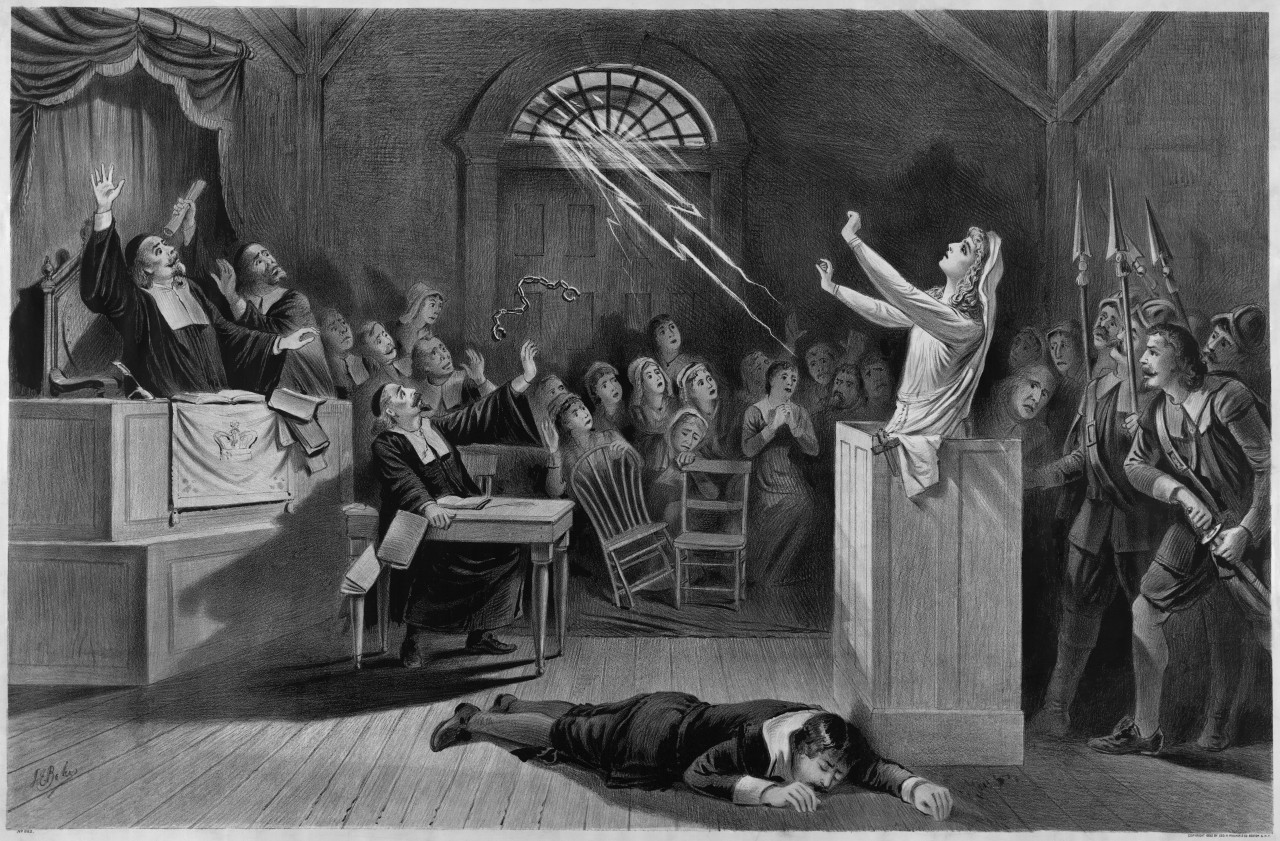

6. Salem Witches And The Burning That Never Happened

The Salem witch trials occupy a dark place in American history, and many people imagine the accused being burned at the stake in a scene borrowed from European witch hunts. The actual records from Salem in 1692 tell a different story. Nineteen people convicted of witchcraft were executed by hanging, not burning. One man, Giles Corey, was pressed to death under heavy stones after refusing to enter a plea. Several others died in prison awaiting trial or judgment. Burning was used in some European regions in earlier centuries, often under different legal traditions, and later art and literature blurred these separate histories together.

7. Columbus, A Round Earth And What People Really Feared

Many school narratives once framed Columbus as the man who proved the Earth was round against a chorus of flat Earth believers in the church and universities. That makes for a simple hero story, but it does not reflect the historical context. Educated Europeans of the late 15th century generally accepted that the planet was spherical, drawing on ancient Greek calculations and widely circulated scholarly texts. Debates about Columbus’s voyage focused on the size of the Earth and the distance to Asia, not on whether the ship would fall off an edge. Critics worried, quite reasonably, that his estimates were too optimistic and that a voyage west would be dangerously long with the ships and supplies available.

8. Roman Soldiers And The Cinema Cloak Palette

Images of Roman legionaries in popular films and paintings often give them deep red, almost theatrical cloaks, sometimes with officers wearing vivid purple capes to signal rank and connection to imperial power. Historically, cloth dyes in antiquity were expensive, variable in quality and not always so saturated. While Roman soldiers did have cloaks to protect against weather, surviving descriptions and textile evidence suggest more practical colors, such as undyed wool or muted shades achieved with common plant dyes. True imperial purple, made from murex shellfish, was extremely costly and restricted by sumptuary rules to elite use. The brightly colored cloaks that appear in art emerged largely from later artistic choices and stage design, where color helped audiences distinguish characters and armies at a glance.

9. Medieval People And The Myth Of Total Filth

The stereotype of the Middle Ages as a time when no one bathed, streets ran with waste and everyone accepted constant filth has been repeated so often that it feels factual. The reality is more nuanced. Medieval cities struggled with sanitation, and outbreaks of disease were real, but written records and archaeological findings show that many communities valued cleanliness within their means. Public bathhouses operated in towns across Europe at various times, households owned basins and linens for washing, and religious rules in some places encouraged regular bathing before prayers or communal events.