Nine chefs who shaped home cooking

Nine chefs clarified home cooking and amplified flavor, bridging French technique and pantry know-how to make weeknights feel doable.

Julia Child

Julia Child popularized French technique in American kitchens by insisting on proven methods, not mystique, and by treating mistakes as normal since the aim was dinner, not perfection. Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1961) explained the reasons behind sauces, roasts, and pastries with practical timing and fixes that keep home cooks moving when something splits, sinks, or browns too quickly. On TV she combined steady humor with calm troubleshooting, teaching to taste, adjust, and serve, and that blend of rigor and warmth gave ordinary weeknights the courage to aim higher.

Marcella Hazan

Marcella Hazan opened Italian home cooking to English-speaking audiences and refused to reduce it to red-sauce shorthand, since Italy’s table rests on decisions, not decorations. In Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking, she taught timeless fundamentals—slow soffritto, careful salting, restraint with herbs, and attention to texture and ingredient quality—that render simple dishes complete. Her clear explanations turned pantry staples like tomatoes, anchovies, butter, and Parmigiano into a reliable system, letting pasta at home taste regional and real rather than a thematic shortcut.

Jacques Pépin

Jacques Pépin redefined home cooking by presenting technique as a language anyone can learn, practice, and trust—rather than a performance reserved for professionals or a source of kitchen anxiety. La Technique (1976) broke down core skills with visual clarity, from knife work to deboning and sauces, so hands could follow without guesswork and cooks could grasp what each motion accomplishes. His calm, recovery-minded teaching showed how to fix things quickly, which is why his influence persists in quiet competence, clean prep, and tastier weeknight meals.

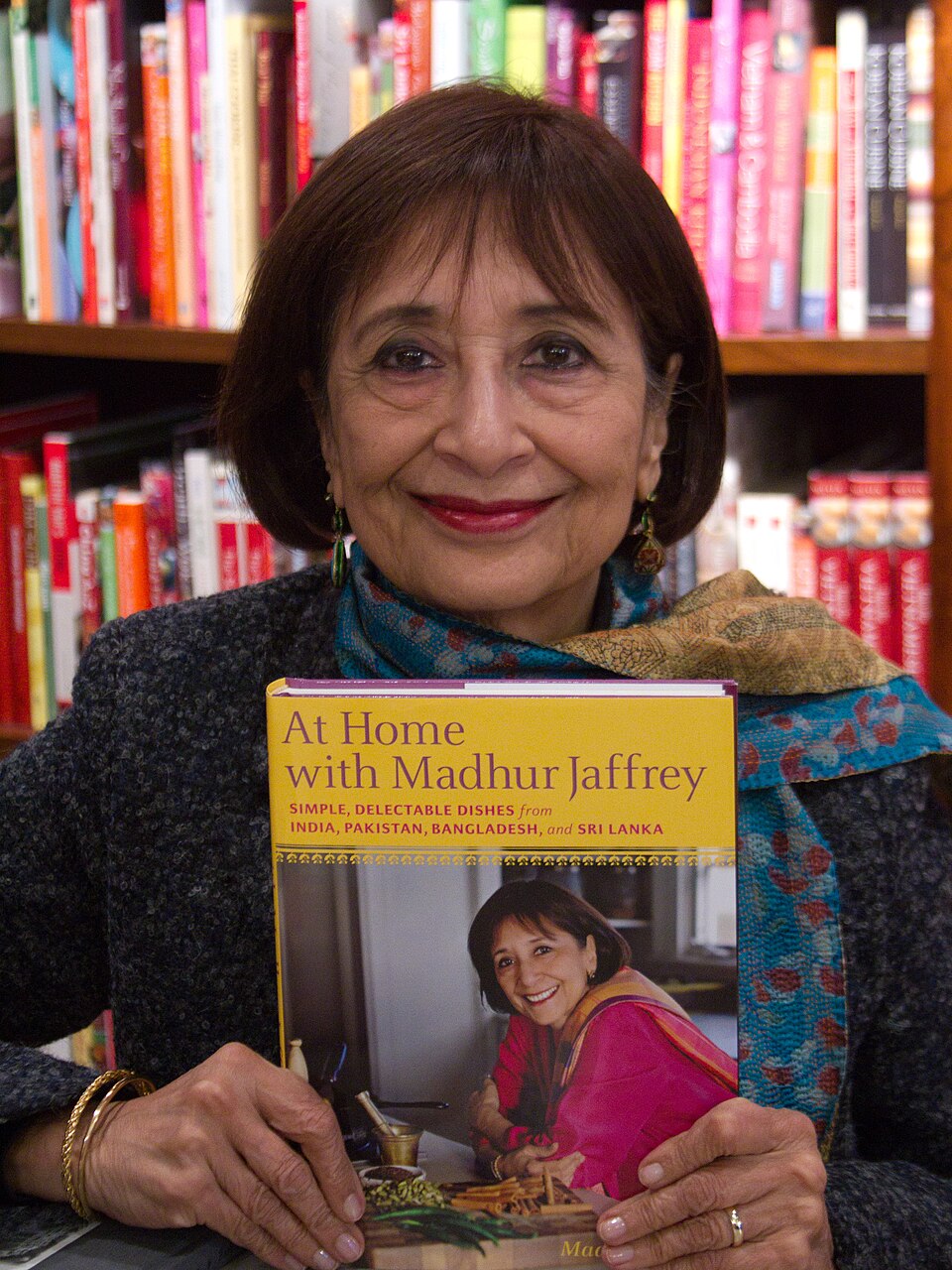

Madhur Jaffrey

Madhur Jaffrey made Indian cooking approachable for Western home kitchens while preserving its character, especially for those who had only encountered the cuisine through restaurants. Madhur Jaffrey’s Indian Cookery (1982) explained spices, tempering, and timing in plain language, turning aromatic depth into a repeatable method and showing how to layer flavor without losing control of heat. She demonstrated how everyday dishes, dals, vegetables, and rice become memorable when the base is built with care, transforming curry from an abstract category into a confident weeknight cooking approach.

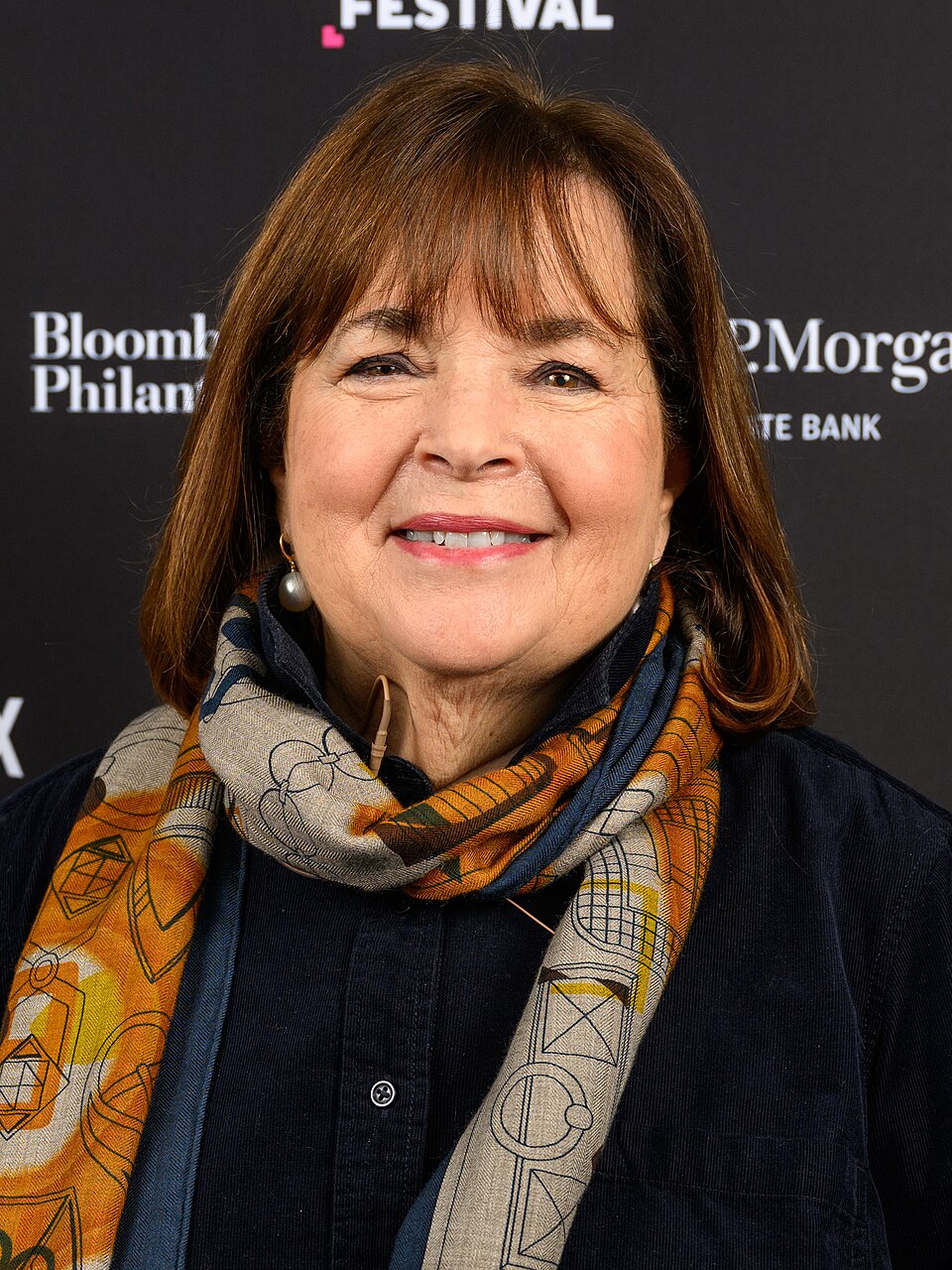

Ina Garten

Ina Garten reshaped home cooking by treating hospitality as a skill with good timing, not a stress test, and by making simplicity feel polished rather than plain, even when the menu is familiar. The Barefoot Contessa Cookbook (1999) leaned on make-ahead thinking, reliable ratios, and recipes that stay steady when life gets busy, guests arrive early, or a cook needs one dependable dish that never fails. She wrote with the confidence of a seasoned host, offering clear choices and smart shortcuts that still feel generous, and that mindset continues to power modern dinners that feel special without being complicated.

Nigella Lawson

Nigella Lawson made home cooking feel personal, comforting, and free of performance, with language that respects appetite rather than lecturing it, and with an eye for what genuinely gets cooked after a long day. In How to Eat (1998) and later books, she treated late-night pasta, warm cake, and a good sandwich as real nourishment, and she explained the small steps that make comfort food feel intentional rather than accidental. By embracing her role as a home cook, she removed perfectionism from the room, helping kitchens regain rhythm where pleasure, practicality, and a touch of indulgence can coexist on an ordinary evening.

Yotam Ottolenghi

Yotam Ottolenghi shifted home cooking toward vegetables, grains, and bold Middle Eastern and Mediterranean flavors, proving meatless meals can feel celebratory, substantial, and worthy of a big platter. Plenty (2010) taught contrast as a habit—sweet with sour, crunchy with silky—and made herbs, citrus, spice, and smart roasting the primary tools for depth, so flavor arrives quickly without heavy technique. He also normalized a fresh pantry—tahini, pomegranate, preserved lemon, za’atar—allowing home cooks to build robust flavor without hours of simmering, and roasted vegetables and salads began to take center stage.

Martha Stewart

Martha Stewart brought structure to home cooking and entertaining by treating it as a craft that could be learned, and by making preparation feel like self-respect rather than fuss. Entertaining (1982) and her later media built a culture of prep lists, smart sequencing, and presentation that signals care, from pacing a menu to finishing a dish so it looks as good as it tastes. Even for cooks who never copy a full tablescape, her influence raised the baseline—better organization, cleaner technique, fewer surprises—and reminded us that polish is planning that protects the joy of feeding people well.

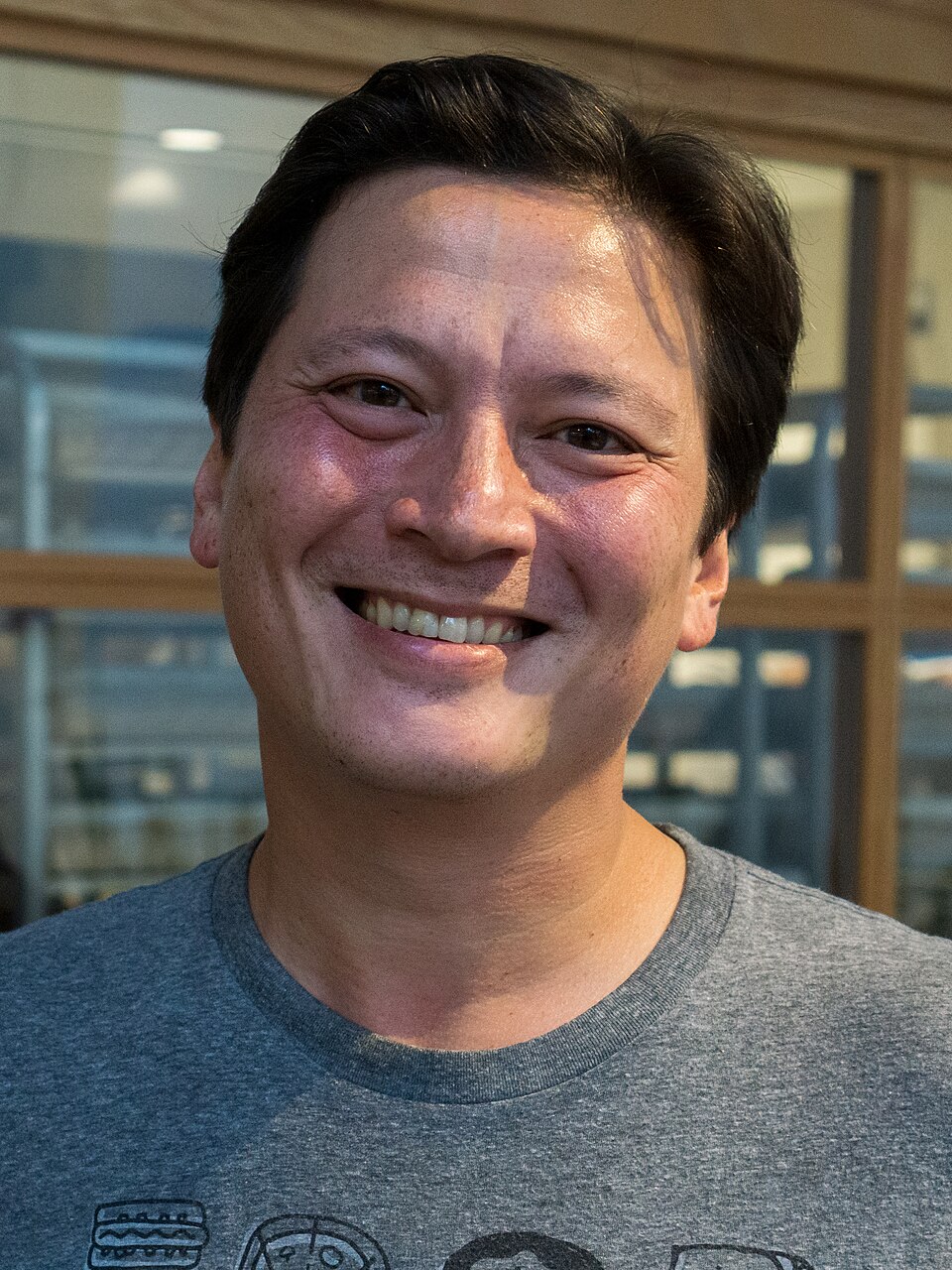

J. Kenji López-Alt

J. Kenji López-Alt modernized home cooking by turning curiosity into dependable method, using testing and clear explanations to replace guesswork, and making food science approachable rather than intimidating. The Food Lab (2015) broke down what heat, moisture, and timing actually do, then translated the results into recipes that work on real stoves, with specific fixes when things go wrong and clear reasons for each step. He reframed mistakes as data, removing shame from learning, and his impact lives in small habits that travel across kitchens—sear harder, salt earlier, and trust a thermometer when instincts run low.