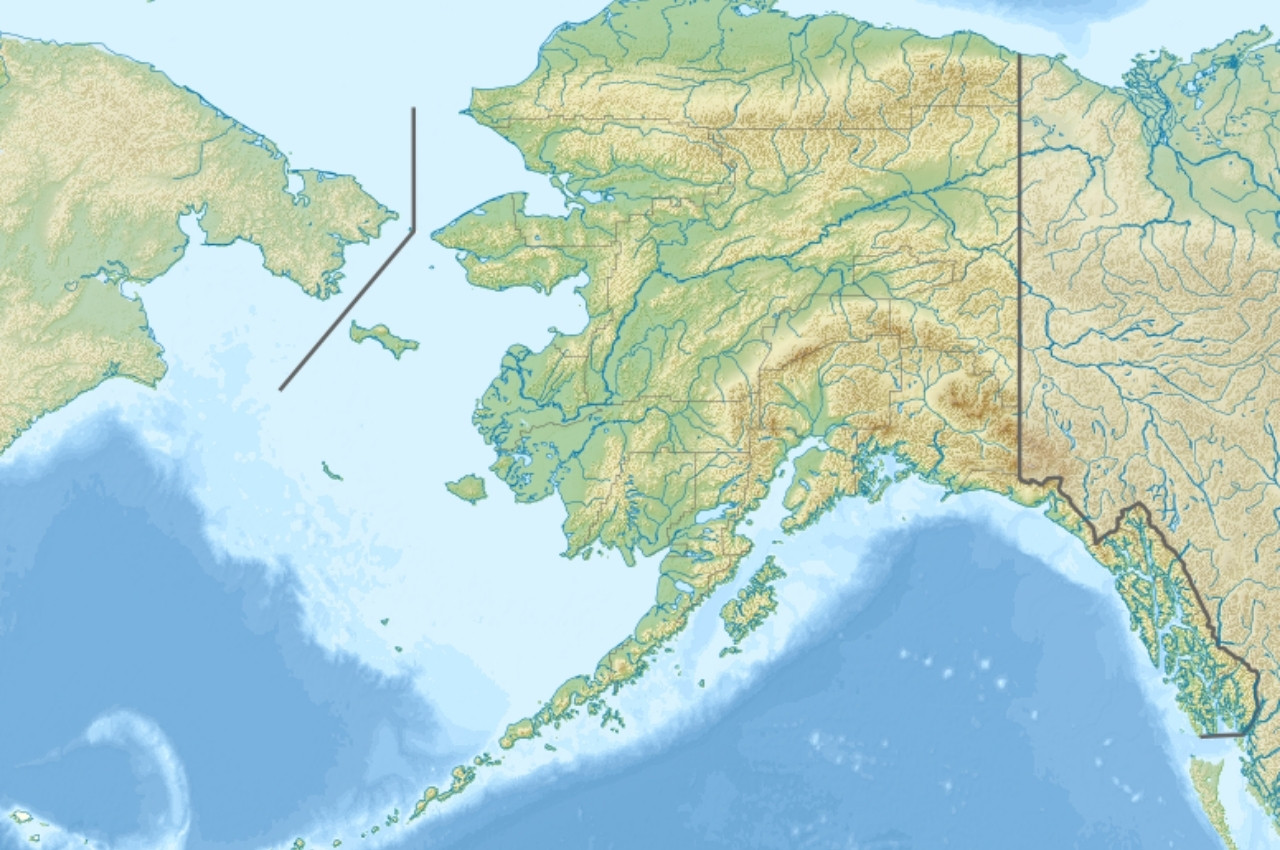

On July 9, 1958, a 7.8–8.3 magnitude earthquake struck the Fairweather Fault in southeast Alaska, triggering a massive landslide into Gilbert Inlet at the head of Lituya Bay.

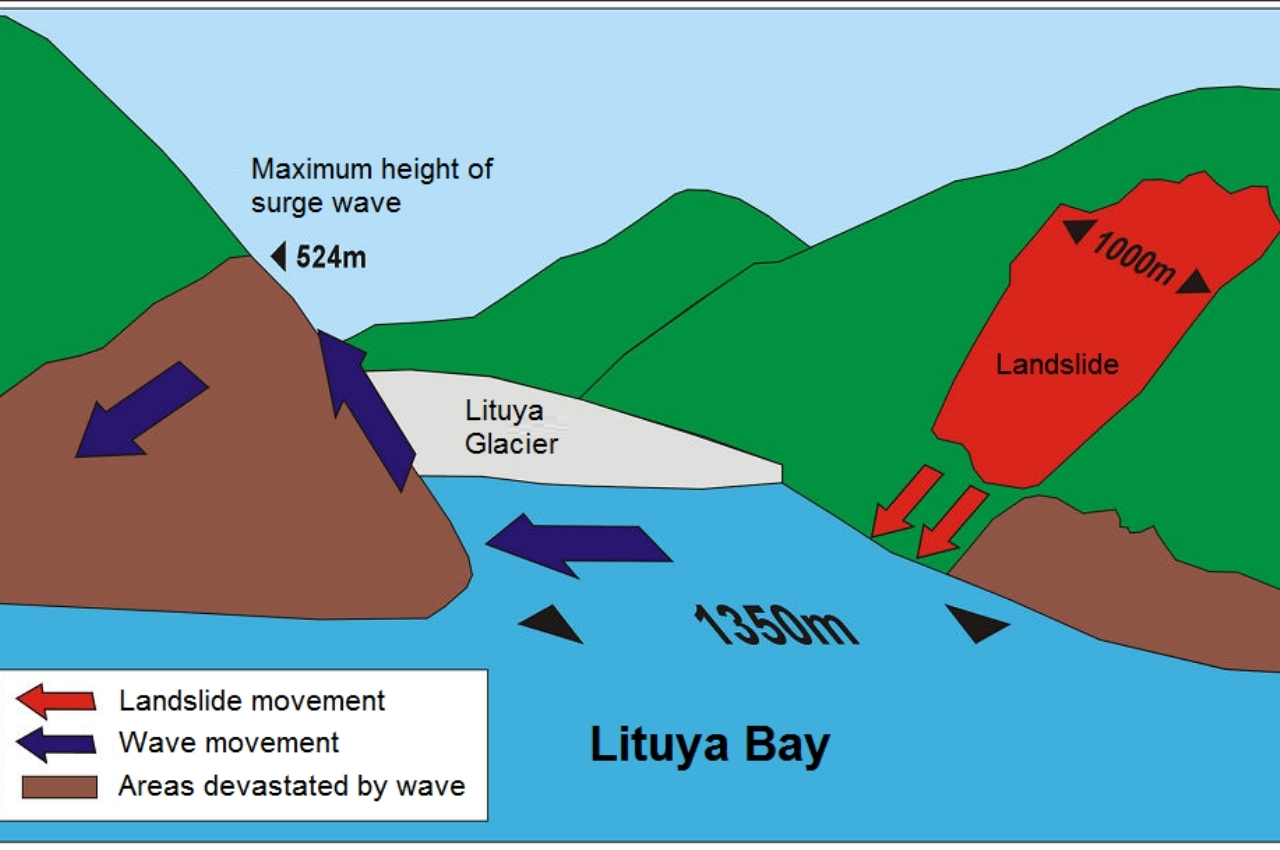

According to the Geophysical Institute of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, about 30 to 40 million cubic yards of rock plunged down a steep slope and displaced enough water to generate what remains the tallest splash wave ever recorded.

The wave’s run-up reached approximately 1,720 feet above sea level, obliterating forests, destroying several boats, and reshaping the geography of Lituya Bay forever.

The Mechanics of the Mega Wave

Lituya Bay is shaped like a “T,” narrow at its entrance and surrounded by steep mountains and glaciers.

According to USGS records, the slope above Gilbert Inlet drops roughly 3,000 feet, and that height contributed heavily to the massive power of the wave.

When millions of cubic yards of rock and debris fell into the water, the displaced water was forced upward and outward.

The wave brushed over hilltops, stripped vegetation all the way to the trimline at 1,720 feet, and raced through the bay at high speed.

The Aftermath: Forests Erased and Landscape Transformed

The force of the 1958 wave was so extreme that it stripped trees, soil, and vegetation from slopes up to 1,720 feet above sea level.

As reported in Giant Waves of Lituya Bay by the Alaska Science Forum, nearby hills and ridges were left bare, exposing bedrock or young saplings where mature trees once stood.

Soil was washed away and replaced by barren, rocky surfaces.

Photographic surveys flown soon after the event revealed massive swathes of destroyed forest and transformed landscapes that were visible from overhead.

Human Toll: Boats, Survivors, and Tragedies

Three fishing boats were anchored or operating in Lituya Bay at the time of the giant wave.

According to USGS and the Alaska Science Forum, one boat near the entrance was sunk, resulting in a husband and wife being killed.

A third boat was carried over La Chaussee Spit into the open ocean, while another boat further inside the bay managed to survive by riding over the wave’s crest.

That boat was swept out by the wave, but amazingly, Howard Ulrich and his young son survived.

Modern Understanding and Ongoing Research

The 1958 Lituya Bay event continues to be studied by scientists who seek to understand megatsunamis and their causes.

Researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey have used digital models and topographical mapping to simulate the landslide and resulting wave behavior.

According to recent findings published in Nature Geoscience, such “impulse waves” differ from oceanic tsunamis because they are confined to enclosed bays or lakes.

Understanding these differences helps scientists develop better hazard assessments for glacial fjords and coastal regions worldwide.

Lessons for Today’s Coastal Communities

The Lituya Bay disaster serves as a stark reminder that not all tsunamis originate from deep-sea quakes.

Some of the world’s most devastating waves can occur in remote bays, where a combination of earthquakes, melting glaciers, and unstable slopes creates ideal conditions.

Alaska, Greenland, and parts of Norway continue to be monitored closely for similar geological setups that could trigger future megatsunamis.

Historical Context: Recurring Giant Waves

Lituya Bay has a documented history of giant splash waves, not limited to the 1958 event.

As noted by the Geophysical Institute, earlier events were reported in 1936, and evidence suggests even older waves occurred in the mid-1800s.

Tree-ring studies, oral histories, and trimline data show that massive waves have occurred several times, each leaving visible scars in the landscape.

Scientists believe that the combination of tectonic activity, heavy mountain slopes, glacial melt, and steep topography makes Lituya Bay especially vulnerable to such events.

Why the 1958 Wave Was Unique

Several factors combined to make the 1958 mega wave far larger than typical tsunamis.

The magnitude of the earthquake triggered the large landslide, and the steep angle and height of the drop magnified its effect.

According to The Big Splash article from the Geophysical Institute, the slope’s geometry, the volume of rock, and the narrow inlet funneled energy.

The wave’s run-up of 1,720 feet remains by far the highest known for any tsunami or splash wave, and it overwrote existing waves from previous events, making them difficult to distinguish afterwards.

References

• Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks – https://www.gi.alaska.edu/alaska-science-forum/giant-waves-lituya-bay

• U.S. Geological Survey – https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/lituya-bay-1958